|

|

|

Shame is present to a certain extent in most of our lives. It's an integral part of being human, of being social entities striving to belong to the group. If our behaviour steps outside of what we think the group wants us to think, see, or feel, then our automatic reaction is shame. In most cases, we learn from these experiences, talk about them with other people, and move on with our lives having learnt a lesson. But there are certain situations that cause shame to bury deep out of sight, affecting how we think about ourselves, and how we live in the world.

0 Comments

The Australian Psychological Society has published their "8 tops for thriving in the digital age." It's a helpful and practical guide to helping navigate the complicated and sometimes distressing needs of social media.

Depression is not simply feeling sad, and not something that people can just "get over" or snap out of. It's an overwhelming self-loathing that saps energy, joy, and hope. Here are some points to help understand more about people who are depressed.

"Anger comes fast, often unanticipated and always unwelcome. It operates without logic, with no concern for consequences. It damages things, relationships, and sometimes even people. It leaves me feeling ashamed of myself. Worthless. What's worse, I'm even too weak and useless to control it."

Does this sound familiar? A study by the Black Dog institute has identified the leading causes of suicide in males in Australia, and at the same time identified some key ways to become involved in the process to help short circuit it.

In 2013, intentional self harm ranked 10th overall in the causes of death for males in Australia, and is the leading cause of death for males aged between 15 and 44. That fact is made even more alarming by the low rate at which men seek help - mirroring the reluctance of men to seek help for depression, or to seek help from a trained professional. What are the signs, and how can you help? People often come to therapy feeling completely overwhelmed by depression and anxiety, by anger or disappointment, confused as to what to do next. People often only come because someone they love has given them an ultimatum - get help or else. The despair that comes into the therapy space is very real, as is the person's belief that they are simply a broken down loser, with no hope, and no right to be. What if you could be separated from that belief, could see that belief is a choice, and begin to build for yourself a different way to be?

It's a powerful statement; one made by Peter Kinderman, Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Liverpool during an interview on BBC radio 4's Today program. I often see clients that have been treated for their depression and anxiety in the "medical model" - That is, symptoms are presented to a GP or a psychiatrist, and those symptoms are treated with medication alone. All too often, those clients report a brief time of improvement, then a gradual worsening of their circumstances. Those individuals suffer a range of additional difficulties as a result of the medical treatment failing, including despair and shame that they are untreatable. Is the medication-only treatment perhaps part of the problem? Forgiveness is being examined in mental health circles with increasing regularity, and the evidence that links forgiveness to mental health is becoming increasingly irrefutable. Forgiveness of others, forgiveness of self, and being forgiven by others are all linked in various ways to depression, particularly as we age. Developing and utilising forgiveness in therapy (and of course life!) is likely to be of great benefit.

The medical model of contemporary psychiatry relies heavily on the prescription of antidepressant medication. Indeed a multi-billion dollar a year industry is dependent on the ongoing prescription of psychotherapeutic medication, in Australia this is a practice largely undertaken by GP's. But what is the real efficacy of this medication. Does it work? And what are the long-term implications of it's use?

Relationship and Family therapist Andrea Wachter wrote an elegant piece in a recent publication outlining 7 things she wished she knew when she was "battling depression." She notes, as is often reported, that it can take a long time to grasp and integrate the tools to ameliorate or banish depressive symptoms. I find them relevant and useful, and have paraphrased her article, adding my own points from the point of view of my own counselling experience.

I am struck, while noting coverage of various ANZAC day ceremonies, how much is made of physical suffering, and how little of the mental scars that accompany war. It's also not just enlisted personnel who suffer. Civilian support staff, local civilians, and those close to sufferers are also directly affected. Contemporary society seems to be in the grip of a self-confidence crisis. I so commonly hear people report that they "have no self-confidence" or "have low self-esteem."

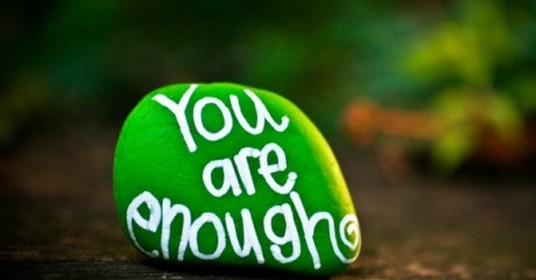

The response of many people to societal demands to be "confident," is to rush around doing constructive, visible things that can give us a sense that we have done what a "confident" person would, or that we've been noticed by others and praised, or that we can compare ourselves to others and feel somehow better than they are. This temporary ego inflation may make us feel good for a while, but it doesn't last. We end up in a cycle of ups and downs that is not only exhausting, but emotionally damaging as well. Ultimately it makes us fundamentally unhappy. One result of this damaging cycle are the innumerable clients who believe that they are "not good enough." As an undergraduate psychology student in the late 1980's, the positive psychology I was exposed to was in the subject of history, where we were duly informed such notions would remain. Unscientific and airy-fairy notions such as "happiness" were not welcome in the hallowed halls of science. Why would this be? The Humanist movement, which aimed to recognise our core human tendencies, was not scientific by definition - it's notions were untestable and therefore results were unpredictable. To a scientific mind that made it less valid than things that are testable and predictable. Life, it would seem, was to be excluded from psychology.

This has thankfully begun to change. |

Author

Chris is a Counsellor and Psychotherapist at Engage Counselling, Sydney Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

Contact: Engage@engagecounselling.com.au

Engage Counselling: Personal and professional Counselling, Coaching and Psychotherapy for men in Sydney's Inner West, Newtown, Enmore, Stanmore, Marrickville, Camperdown, Chippendale, St Peters, Erskineville, Pyrmont, Darling Harbour, Balmain, Sydney, City, Broadway, Ultimo, CBD and surrounding suburbs.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed